Stage 3 is the last time a level divides itself into three distinct parts. It's easily the most dramatic of the tripartite stages, with its elements of vertical progress and the return to the upper world, and its sections' different musical tracks. Yet it also feels the quietest of the treks thus far, due in large part to block 3-2 and the music's general mellowness. Our watery path has taken us to a cave populated by mud men, bats, and bone pillars. There are no deadly pits here -- just the occasional bed of spikes, which I like to imagine as thorny cave formations, rather than as the literal videogame trope.

Aside from stage 5, stage 3's blocks 3-1 and 3-2 are SCV4's most easy-going spots -- interesting, since block 3-3 is, as I said in a previous article, the section that is likeliest to stand out to players as the first time that the game demands more than just a standard level of attentiveness. But let's be clear: block 3-3 is not some hellish gauntlet. It's simply a few steps up from where we were before. Let's also be clear that SCV4's difficulty does not linearly escalate -- that is, one stage is not necessarily tougher to cover than a stage before it just because it comes after. Although I sympathize with people who yearn for a progression of difficulty akin to, say, Castlevania, I also feel -- as I do about the visuals -- that enjoyment can be gleaned from SCV4's uneven progression, provided one is not prepared to dismiss the unevenness on the basis of that alone. This is a game with a lot of breathing space, and a game that asks to have that breathing space admired.

It's significant that SCV4 is a continuation -- a SUPER continuation -- of a series that, around its time, had pretty much solidified itself as a home to hearty, burly action; and yet the game presents itself as, to borrow a phrase (although I know he did not coin it) from YouTube user Errant Signal, a tone piece, and one that, while spectacular in its own way, sidesteps (or walks away from) the bombast or emotional immediacy one might assume it would pursue. We can hypothesize different reasons for why games had, or allowed for, more room for "introversion" -- for approaches that favored forms of quietness, or things outside of the realm of Non-Stop Action -- as technology progressed, but SCV4 was made at a time when "extroversion" was such a dominant aesthetic that to make the generalization that it was the only aesthetic doesn't seem too unfair. And it's all the stranger since this game is, to a degree, still guided by the kitschy horror elements of its forebears.

You can reach a hidden chamber full of goodies here if you whip a bunch of uniquely shaped, and unnaturally (relative to the game) assembled, rocks. This is the first time that SCV4 lets players know that it holds secrets that are a bit more extensive than walls whose first layer can be chipped away. Check out the messy, cut-up arrangement of tiles for the brownish speleothems in these screenshots. Despite occasional snags, such as where the tiles have a clean horizontal slice on the tops or bottoms, the disorganized layering of stuff helps to further the formations' strangeness. A more obvious and appealing sight is the far background, whose columns, stalagmites, and stalactites are of a green, almost luminescent hue. Pure black pokes out from the view's furthest reaches, giving us the sense that, although the path we must take is short, the cave's total scope is massive.

Near the block's end, a few rows of stalactites quiver ominously. Of course, these stalactites do fall, but they can all be passed by before then if one keeps pressing on (a minor callback to the momentous dynamic that informed so much of the first Castlevania) -- except for the last row, where a mud man (see the third screenshot of this entry) patrols the ground below and must first be destroyed for safe passage, necessitating a tiny retreat and pause. The mud men are very obviously technical wonders and little else (very slow; no offensive options), existing so that players in 1991 could've marveled when they whipped the enemy and saw it split into two smaller versions of itself, each of these splitting into a pair of even smaller versions with two further whips. During these divisions, the particle effects take a massive chunk out of the framerate, so it's perhaps a good thing that mud men exist in low-risk spots.

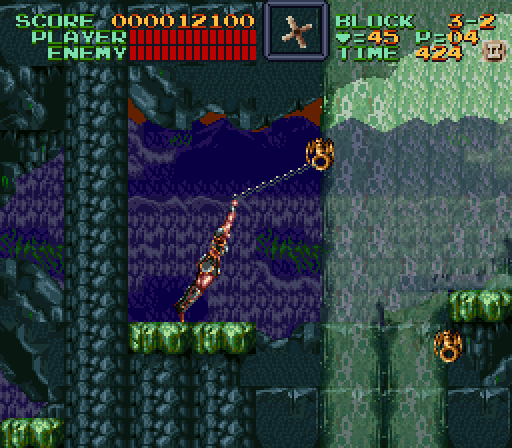

Exiting from the cave, we find ourselves near the bottom of a series of greenish falls, and faced with the task of scaling a series of rocky platforms jutting out from a natural wall. Technically, there's not a lot to talk about here. Block 3-2 is a glum intermediary between the first and third blocks. The unmitigated ascent helps to impart the idea that Simon is working towards an environmental climax, yet there are almost no parts in the game that are as tranquil as this; and there are definitely no other blocks that house such sparse, anchored music. Bone pillars, unes, slow-moving bats, and fizzling orbs that guard the boundaries of platforms (first appearing in CV3) are all you have to deal with. Whip-swinging comes into play again, although it remains an unmarried interactive dynamic, not yet complemented by complicating enemy placement or spatial design.

Block 3-2 shows off another unusual mixture of colors, and one that, like several others in the game, inescapably makes me think of the palettes of some German expressionist paintings. Of special interest is the perplexing backdrop depicting what appears to be a forest (very curious representation here: jagged, vertical etchings with a severe absence of depth and perspective) and mountain range, all cast in deep purple shadow, and a brown-red sky above. Have we emerged into sunset, sunrise, or a timeless zone in between? More ambiguity. There are plenty of candles along the path. Most players will probably acquire close to the maximum number of hearts (ninety-nine) by block 3-2's end. Keep in mind that this is still part of stage 3! Getting the maximum number of hearts two-thirds of the way through a stage in, say, CV3 never would have happened. Running out of hearts, or having a low amount, is not a thing that will occur very often in SCV4, unless you're dying a lot and using subweapons as if they're your main weapon.

Speaking of subweapons, I've forgotten to bring up a mechanical change SCV4 makes. Beforehand, subweapons were used by pressing the attack button and up on the D-pad at once. This conflicted with the usage of staircases, since the necessity of pressing up to use a subweapon could make a player's stair-climbing avatar walk up a step before attacking. It's understandable why this was the way of things -- there were only so many buttons on the NES' controller -- and, sure, having a little wrinkle in the subweapon mechanic that was tied to site-specificity was sort of cute, but it remained a consequence of the less interesting variety of limitation (that is, literally how many buttons were on the controller). SCV4 has the benefit of the SNES controller's greater buttons, and so it maps subweapon control to the R button on the right hand shoulder. Problem solved!

At the top of block 3-2, Simon has to make a barely-made-it leap onto a ledge leading to the next block. A pair of columns indicates that we're entering a less natural environment. We also can see the top of the waterfall. The source must be nearby.

But it's over with almost as soon as it starts, and we're onto our first bone dragon, seen at the right edge of the screenshot below. Similar to other imported enemies, not enough has been done to the bone dragon -- it still sprouts out from a wall, wiggles upwards and downwards, and spits out the occasional straight fireball -- to make it a match for the new Simon. SCV4's enemies, like those in the NES trilogy, pause for a split second when they are hit by the whip or a subweapon. This carry-over, combined with Simon's octo-directional whip and the bone dragon's behaviorism, means that players can walk up to and stand under the enemy when its body and head are above Simon and whip upwards a good number of times before the bone dragon lowers itself. Even so, bone dragons are hardy and erratic enough to be at least more of a threat than bone pillars.

Block 3-3's most impressive asset is its music, a dynamic jazz piece in 3/4 time, full of rhythmic surprises, passages with an improvisational flavor, and lead trade-offs that give the sense that a virtual performance is happening. There is no other music on the system that is exactly comparable. Highlighting this track also calls to mind the point that, as technology allowed more aesthetic freedoms, Castlevania incorporated into its qualities an appeal based upon unexpected unions. To be sure, that appeal was already present from the start, but it was more or less limited to the straightforward contrast between the games' horror-derived motifs and the charged, highly melodic music. But with SCV4, we start to get a richer array of medleys, an example of which is this mixture of "free-jazz" and "classical" architecture. One of the greatest mistakes of the recent Castlevania titles is that they have lost this contrast; instead, the developers have obsessed over an appropriateness between narrative, visuals, and audio. The irony is that such a confluence yields only drudgery, because what is appropriate is what is expected, and what is expected in a series about hyper-masculine men killing monsters is the cliche. Lords of Shadow's music is "dark" and "cinematic" because the game is "dark" and "cinematic." Appropriateness has long threatened the series, like a phantom, and it would've been an easy thing to succumb to each step of the way. Although I want to say that it was the games' Japanese teams that allowed for this oddness to develop, I can't; there are different levels to the eccentricity on display in Konami titles. Rather, I think it was a mixture of that non-Western handling of Western elements and the creative powers of those doing the handling.

Once we've climbed a staircase to an upper course, the mermen assume a relative passivity by remaining in the water, after they've swum up from below, and spitting out angled shots of water. The best way to avoid this is by pressing on. With the presence of minor but potentially irritating enemies such as the fire eye (a floating eyeball that pauses here and there to drip a fireball) or une, and the reappearance of the whip latches in more demanding zones (players must respect the possibility of a merman coming up beneath them when they're swinging across a watery gap), a series-roots momentum -- or a need for momentum -- appears that thus far has lain dormant.

The last room is a climb to the boss, and has a couple of curiously placed bone dragons. Rectangular openings in the wall all of a sudden spring links while you ascend, and if you get under the waterfalls there's a nice, existence-acknowledging bubbling effect around Simon's body. Seen below is the first bone dragon, and, as you can tell by what Simon is doing, it's possible to under-attack the creature without putting yourself in harm's way. The second bone dragon's position, too high to interfere with a nearby whip latch and too low to block off a mandatory staircase, effectively makes it a warning, and not a thing you must deal with. You can, however, take care of it if you're so compelled.

Three divebombing crows are the realest threat along the way here, coming down upon Simon as he's scaling a staircase that's a few tiers away from the boss. It's half-cheap and half-smart: their convergence is almost too quick for novices to reasonably avoid being hit once, but they are a justification for the octo-directional whipping in a game that has a dearth of such justification. It's best to stay on the staircase and take care of all three. Making it to the level above with a remaining bird or two runs you the risk of being hit by one and getting knocked into the pit on the right.

I'm happy to say that this is not an auto-scrolling section. CV3 introduced those, and they were infuriating -- vertical parts wherein, every three seconds, the screen shuddered and, with a crash, moved up two brick-widths. This was a bad idea for two reasons: 1) you had to moderate how fast you ascended, as enemies' sprites could generate on top of you once the screen caught up to your spot; 2) the scrolling had no in-game basis, and was reducible to "Because Videogames." Number two felt especially egregious when you realized that nothing else in the game's level design worked this way. These were moments where atmosphere and context were rubbed out in favor of challenge.

Additional wall-openings gush out liquid at the top and raise the water level up to the lowest platform. With this, the fight begins. Stage 3's boss, the Orphic Vipers, can be seen as a glorified couple of bone dragons. Both weave up and down, and back and forth (but never forward enough to hit where Simon is in the screenshot), and both have the ability to project flames from their mouths (one shoots out three fireballs in a spray pattern, and the other ejects a static flame with limited range). All that's required to win this fight is keeping your distance and making sure that one of the three fireballs shot from the respective serpent head doesn't hit you. As usual, having the cross subweapon is a huge help. CV3's Water Dragons, with their guessing-game behavior, limited openings, and their room's dangerous, tight layout, constituted a much more interesting tussle than this. SCV4's Vipers burn up and collapse into the water as skeletons upon their defeat.

Dracula's castle nears. In the next entry, stage 4, the bizarre Sorcery Tower, will be our subject.

No comments:

Post a Comment