Stage 3 is the last time a level divides itself into three distinct parts. It's easily the most dramatic of the tripartite stages, with its elements of vertical progress and the return to the upper world, and its sections' different musical tracks. Yet it also feels the quietest of the treks thus far, due in large part to block 3-2 and the music's general mellowness. Our watery path has taken us to a cave populated by mud men, bats, and bone pillars. There are no deadly pits here -- just the occasional bed of spikes, which I like to imagine as thorny cave formations, rather than as the literal videogame trope.

Aside from stage 5, stage 3's blocks 3-1 and 3-2 are SCV4's most easy-going spots -- interesting, since block 3-3 is, as I said in a previous article, the section that is likeliest to stand out to players as the first time that the game demands more than just a standard level of attentiveness. But let's be clear: block 3-3 is not some hellish gauntlet. It's simply a few steps up from where we were before. Let's also be clear that SCV4's difficulty does not linearly escalate -- that is, one stage is not necessarily tougher to cover than a stage before it just because it comes after. Although I sympathize with people who yearn for a progression of difficulty akin to, say, Castlevania, I also feel -- as I do about the visuals -- that enjoyment can be gleaned from SCV4's uneven progression, provided one is not prepared to dismiss the unevenness on the basis of that alone. This is a game with a lot of breathing space, and a game that asks to have that breathing space admired.

It's significant that SCV4 is a continuation -- a SUPER continuation -- of a series that, around its time, had pretty much solidified itself as a home to hearty, burly action; and yet the game presents itself as, to borrow a phrase (although I know he did not coin it) from YouTube user Errant Signal, a tone piece, and one that, while spectacular in its own way, sidesteps (or walks away from) the bombast or emotional immediacy one might assume it would pursue. We can hypothesize different reasons for why games had, or allowed for, more room for "introversion" -- for approaches that favored forms of quietness, or things outside of the realm of Non-Stop Action -- as technology progressed, but SCV4 was made at a time when "extroversion" was such a dominant aesthetic that to make the generalization that it was the only aesthetic doesn't seem too unfair. And it's all the stranger since this game is, to a degree, still guided by the kitschy horror elements of its forebears.

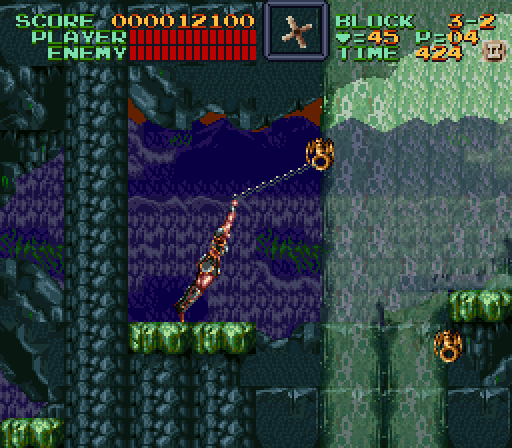

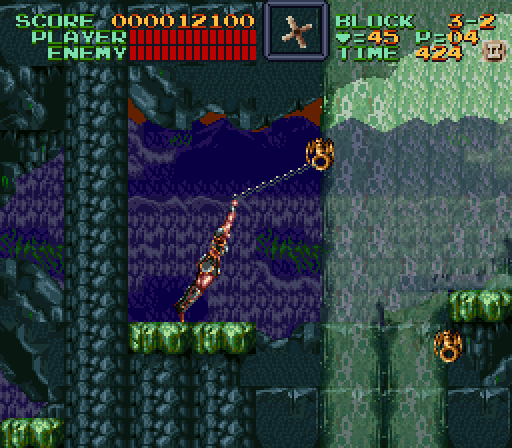

You can reach a hidden chamber full of goodies here if you whip a bunch of uniquely shaped, and unnaturally (relative to the game) assembled, rocks. This is the first time that SCV4 lets players know that it holds secrets that are a bit more extensive than walls whose first layer can be chipped away. Check out the messy, cut-up arrangement of tiles for the brownish speleothems in these screenshots. Despite occasional snags, such as where the tiles have a clean horizontal slice on the tops or bottoms, the disorganized layering of stuff helps to further the formations' strangeness. A more obvious and appealing sight is the far background, whose columns, stalagmites, and stalactites are of a green, almost luminescent hue. Pure black pokes out from the view's furthest reaches, giving us the sense that, although the path we must take is short, the cave's total scope is massive.

Near the block's end, a few rows of stalactites quiver ominously. Of course, these stalactites do fall, but they can all be passed by before then if one keeps pressing on (a minor callback to the momentous dynamic that informed so much of the first Castlevania) -- except for the last row, where a mud man (see the third screenshot of this entry) patrols the ground below and must first be destroyed for safe passage, necessitating a tiny retreat and pause. The mud men are very obviously technical wonders and little else (very slow; no offensive options), existing so that players in 1991 could've marveled when they whipped the enemy and saw it split into two smaller versions of itself, each of these splitting into a pair of even smaller versions with two further whips. During these divisions, the particle effects take a massive chunk out of the framerate, so it's perhaps a good thing that mud men exist in low-risk spots.

Exiting from the cave, we find ourselves near the bottom of a series of greenish falls, and faced with the task of scaling a series of rocky platforms jutting out from a natural wall. Technically, there's not a lot to talk about here. Block 3-2 is a glum intermediary between the first and third blocks. The unmitigated ascent helps to impart the idea that Simon is working towards an environmental climax, yet there are almost no parts in the game that are as tranquil as this; and there are definitely no other blocks that house such sparse, anchored music. Bone pillars, unes, slow-moving bats, and fizzling orbs that guard the boundaries of platforms (first appearing in CV3) are all you have to deal with. Whip-swinging comes into play again, although it remains an unmarried interactive dynamic, not yet complemented by complicating enemy placement or spatial design.

Block 3-2 shows off another unusual mixture of colors, and one that, like several others in the game, inescapably makes me think of the palettes of some German expressionist paintings. Of special interest is the perplexing backdrop depicting what appears to be a forest (very curious representation here: jagged, vertical etchings with a severe absence of depth and perspective) and mountain range, all cast in deep purple shadow, and a brown-red sky above. Have we emerged into sunset, sunrise, or a timeless zone in between? More ambiguity. There are plenty of candles along the path. Most players will probably acquire close to the maximum number of hearts (ninety-nine) by block 3-2's end. Keep in mind that this is still part of stage 3! Getting the maximum number of hearts two-thirds of the way through a stage in, say, CV3 never would have happened. Running out of hearts, or having a low amount, is not a thing that will occur very often in SCV4, unless you're dying a lot and using subweapons as if they're your main weapon.

Speaking of subweapons, I've forgotten to bring up a mechanical change SCV4 makes. Beforehand, subweapons were used by pressing the attack button and up on the D-pad at once. This conflicted with the usage of staircases, since the necessity of pressing up to use a subweapon could make a player's stair-climbing avatar walk up a step before attacking. It's understandable why this was the way of things -- there were only so many buttons on the NES' controller -- and, sure, having a little wrinkle in the subweapon mechanic that was tied to site-specificity was sort of cute, but it remained a consequence of the less interesting variety of limitation (that is, literally how many buttons were on the controller). SCV4 has the benefit of the SNES controller's greater buttons, and so it maps subweapon control to the R button on the right hand shoulder. Problem solved!

At the top of block 3-2, Simon has to make a barely-made-it leap onto a ledge leading to the next block. A pair of columns indicates that we're entering a less natural environment. We also can see the top of the waterfall. The source must be nearby.

And here's the source -- the partly submerged ruins of a Grecian complex. Silhouetted temples rest against a purple sky, and the fluted trunks of columns rise from deep blue water. Block 3-3 is an unmistakable reference to CV3's Sunken City of Poltergeists, right down to its minor enemies (skeletal knights, bone dragons, mermen) and boss (a pair of huge, aquatic serpents). After Bloodlines and Dracula X, this theme disappears, excepting its halfhearted revival in Curse of Darkness. Players are introduced to the block in somewhat awkward fashion. Right after a very short route where mermen leap out of the water and land on solid surfaces, players must jump across a handful of tiny platforms, some being the kind that crack apart and fall if they're stood on for more than several seconds. At the same time, a few harmless rocks fall from the sky; these are meant to be a warning that four big, harmful chunks of columns are about rain down, one at a time -- but the player is likely to be too confused by the harmless shower and hurried by the crumbling platforms to intuit this follow-up. It's not the best sequence, and it's further hurt by its lack of a precedent. Levelheaded players with sure footing might stand by and wait for the column chunks to finish falling.

But it's over with almost as soon as it starts, and we're onto our first bone dragon, seen at the right edge of the screenshot below. Similar to other imported enemies, not enough has been done to the bone dragon -- it still sprouts out from a wall, wiggles upwards and downwards, and spits out the occasional straight fireball -- to make it a match for the new Simon. SCV4's enemies, like those in the NES trilogy, pause for a split second when they are hit by the whip or a subweapon. This carry-over, combined with Simon's octo-directional whip and the bone dragon's behaviorism, means that players can walk up to and stand under the enemy when its body and head are above Simon and whip upwards a good number of times before the bone dragon lowers itself. Even so, bone dragons are hardy and erratic enough to be at least more of a threat than bone pillars.

Block 3-3's most impressive asset is its music, a dynamic jazz piece in 3/4 time, full of rhythmic surprises, passages with an improvisational flavor, and lead trade-offs that give the sense that a virtual performance is happening. There is no other music on the system that is exactly comparable. Highlighting this track also calls to mind the point that, as technology allowed more aesthetic freedoms, Castlevania incorporated into its qualities an appeal based upon unexpected unions. To be sure, that appeal was already present from the start, but it was more or less limited to the straightforward contrast between the games' horror-derived motifs and the charged, highly melodic music. But with SCV4, we start to get a richer array of medleys, an example of which is this mixture of "free-jazz" and "classical" architecture. One of the greatest mistakes of the recent Castlevania titles is that they have lost this contrast; instead, the developers have obsessed over an appropriateness between narrative, visuals, and audio. The irony is that such a confluence yields only drudgery, because what is appropriate is what is expected, and what is expected in a series about hyper-masculine men killing monsters is the cliche. Lords of Shadow's music is "dark" and "cinematic" because the game is "dark" and "cinematic." Appropriateness has long threatened the series, like a phantom, and it would've been an easy thing to succumb to each step of the way. Although I want to say that it was the games' Japanese teams that allowed for this oddness to develop, I can't; there are different levels to the eccentricity on display in Konami titles. Rather, I think it was a mixture of that non-Western handling of Western elements and the creative powers of those doing the handling.

Once we've climbed a staircase to an upper course, the mermen assume a relative passivity by remaining in the water, after they've swum up from below, and spitting out angled shots of water. The best way to avoid this is by pressing on. With the presence of minor but potentially irritating enemies such as the fire eye (a floating eyeball that pauses here and there to drip a fireball) or une, and the reappearance of the whip latches in more demanding zones (players must respect the possibility of a merman coming up beneath them when they're swinging across a watery gap), a series-roots momentum -- or a need for momentum -- appears that thus far has lain dormant.

The last room is a climb to the boss, and has a couple of curiously placed bone dragons. Rectangular openings in the wall all of a sudden spring links while you ascend, and if you get under the waterfalls there's a nice, existence-acknowledging bubbling effect around Simon's body. Seen below is the first bone dragon, and, as you can tell by what Simon is doing, it's possible to under-attack the creature without putting yourself in harm's way. The second bone dragon's position, too high to interfere with a nearby whip latch and too low to block off a mandatory staircase, effectively makes it a warning, and not a thing you must deal with. You can, however, take care of it if you're so compelled.

Three divebombing crows are the realest threat along the way here, coming down upon Simon as he's scaling a staircase that's a few tiers away from the boss. It's half-cheap and half-smart: their convergence is almost too quick for novices to reasonably avoid being hit once, but they are a justification for the octo-directional whipping in a game that has a dearth of such justification. It's best to stay on the staircase and take care of all three. Making it to the level above with a remaining bird or two runs you the risk of being hit by one and getting knocked into the pit on the right.

I'm happy to say that this is not an auto-scrolling section. CV3 introduced those, and they were infuriating -- vertical parts wherein, every three seconds, the screen shuddered and, with a crash, moved up two brick-widths. This was a bad idea for two reasons: 1) you had to moderate how fast you ascended, as enemies' sprites could generate on top of you once the screen caught up to your spot; 2) the scrolling had no in-game basis, and was reducible to "Because Videogames." Number two felt especially egregious when you realized that nothing else in the game's level design worked this way. These were moments where atmosphere and context were rubbed out in favor of challenge.

Additional wall-openings gush out liquid at the top and raise the water level up to the lowest platform. With this, the fight begins. Stage 3's boss, the Orphic Vipers, can be seen as a glorified couple of bone dragons. Both weave up and down, and back and forth (but never forward enough to hit where Simon is in the screenshot), and both have the ability to project flames from their mouths (one shoots out three fireballs in a spray pattern, and the other ejects a static flame with limited range). All that's required to win this fight is keeping your distance and making sure that one of the three fireballs shot from the respective serpent head doesn't hit you. As usual, having the cross subweapon is a huge help. CV3's Water Dragons, with their guessing-game behavior, limited openings, and their room's dangerous, tight layout, constituted a much more interesting tussle than this. SCV4's Vipers burn up and collapse into the water as skeletons upon their defeat.

Dracula's castle nears. In the next entry, stage 4, the bizarre Sorcery Tower, will be our subject.

Onto stage 2. Like stage 1, it is divided into three zones: a wood, a swamp, and a river. We got a glimpse of it at the end of the last post. The level of challenge increases, but only minimally. It likely will not be until stage 3's last segment that players will notice a spike in what is demanded of them. For now, we're still given enough of a margin for error that we can more ably admire the game's atmospherics. Bright foliage set against a furrowed, sagging sky combine to craft a mental scent -- the smell of the air before a storm, or just after it. There's a good chunk of curious, perhaps even inscrutable, level design decisions on display here; but this remains one of my favorite stages in the game for how richly it conveys an atmosphere of fragrant decomposition.

Further connections to CV3 appear in the form of the spiders that descend via silky threads, pause to shoot a smaller spider your way, and reverse (descending again after they've gone offscreen). Only a couple appear along this trail in definite spots, and once they've been taken care of that's the end. With Simon's octo-directional whipping, they're no problem at all. Purple hands of the undead dig out of the soil in random spots and latch onto Simon's legs, holding him in place. Mashing on the d-pad or the jump button enough times will shake them loose. In truth, they're merely a nuisance, since the only other adjacent enemies you'll run into are the spiders and a couple of invisible wraiths that use leaves to assume a humanoid form and hop out of the background, patrolling a plot of land (like a few other enemies in the game, the only threat they pose is the suddenness of their emergence).

Shown above, the dip in the landscape that was previewed in Study No. 2.5, and further evidence of the SCV4's unique aesthetic vision. Gnarled, gold-brown blocks of dirt and rock are set against the hard gray horizontal ribbons of a great natural wall, its open wounds stitched by purple roots; and behind, another wall that has its tightly packed surface encrusted by orange geologic masses. Small animals called needle lizards occupy four spaces here. Although their offensive tactic -- curling into a ball and rolling in one direction at a high speed -- doesn't really necessitate a tutorial of sorts, the geography here allows players to whip the critters without needing to be on the same plane as them. Thorough people will find that a leap of faith yields a cross subweapon.

We emerge from brief submersion to see that the terrestrial backdrop has developed into four separately scrolling layers to match the skyscape's visual depth. I've included this shot for the detail on the upper left, easy to miss since it blends in with the sky and doesn't stay onscreen for long. We can see what looks like a structure (a castle? If so, it's not Dracula's) perched atop a ledge -- a ledge that would seem to be far off because of the pointed sprouts of coniferous trees below. Why is this strange? Because these details are part of the foreground, meaning that they scroll by at a rate equal to that of Simon's movement. It's a bit hard to interpret this as something other than a mistake on the developers' part -- and yet, who knows for certain? Are those coniferous trees really trees? Is that structure really a castle?

A brief path with one needle lizard, two invisible wraiths, and shambling zombies birthed from the soil leads to stage 2's second segment. Falling into the muddy waters of block 2-2 isn't fatal -- as in CV3, players who do fall in will just need to be sure that they're not drawn down all the way by consistently jumping. Une plants (their sprite was reused as recently as Order of Ecclesia!), bats, crows, skeletons, frogs, and needle lizards inhabit these parts, positioned fairly independently. The crows, whose dark colors match the also-dark backgrounds and whose behavior isn't as hard-set as it was on the NES (they might swoop at Simon right after alighting from their perches, or they might pause for an instant) could cause trouble for the first-timers. So could the couple of frogs, due to their unpredictable leaping and small bodies; they're very weak, though, and can be taken care of by one whip dangle. Players can try to bypass the first frog via a route of upper platforms, but will need to mind a skeleton and crow.

Block 2-2 sports a handful of mobile floating platforms. These first appeared in the fourth room of Castlevania's second stage. They've never had an existentially intelligible reason for being (among architecture that, while practically unintelligible, has often been complemented by purely visual, structurally explanatory details (check out the screenshot above for an immediate example)), but I think there has to be some wiggle-room for whits of nonsense. If I were to be critical, I might say that it'd make more sense for floating platforms to be in Dracula's castle, a setting that pairs better with abnormal physical laws than the outdoors.

Our move to block 2-2 has brought us to a higher elevation. Simon uses a vertically floating platform to reach a couple of bridges. It's cool to see that Konami differentiated the two, rather than copy-pasting one. Simon's weight causes the planks to sag under him on the second bridge, and jumping up and landing makes the ropy rails wiggle. Three well-obscured crows are perched along this passage. I should take this opportunity to say that stage 2's music, "Forest of Evil Spirits," couldn't be better. An insistent, hunched groove played on a bass guitar guides things along at a steady pace, helped by the sharp, woody percussion. Above, an eclectic mixture of instruments trade places for the lead role -- an organ, a woodwind, faded strings, a harpsichord, and a horn. The track's chugging drive is a perfect match for the hurried clouds and the upcoming river's flow.

I should also take this opportunity to say that the knife subweapon (screen one, above) somewhat reprises the role it had in CV3 as a pest. It's too bad that Konami decided to run with this after apparently realizing that the subweapon was, by far, the least desirable of the bunch in the first game. It took until Rondo of Blood for the knife to assume legitimate place among the subweapons, thanks to the inclusion of the item crash mechanic (although its direct descendent, Bloodlines, just nixed the knife entirely). Getting the knife in SCV4 doesn't matter nearly as much as it did in CV3 because of the array of options afforded by the whip's alterations and the lower challenge level, but it's still a downer when you accidentally grab it. Some might argue that this makes whipping candles more of a thought-intensive, and thus interesting, action (since you need to have Simon out of the way of a relinquished object, should it be a knife), but the demonization of a mechanical feature doesn't strike me as admirable design. While it may very well be more interesting, distrusting every candle among hundreds surrounds the dynamic with the pallid hue of paranoia.

Medusa is the mid-boss, and only boss, of the stage, as indicated by the bat icon on the map. CV3 had a similar moment wherein players fought Medusa and, upon winning, realized that the ghost ship stage wasn't over -- that there was more of it to traverse and that a greater threat was at the end of this trial. SCV4 only mimics the first half of that follow-up, because its final lap leads to stage 3. It's sort of a curious design decision, considering that it only happens once. Every other stage, mini-boss or no, has a boss at its very end. Medusa is the simplest of any lifebar'd enemy to defeat. Go in with whip whistling and subweapons hurling and she'll drop in a few seconds flat. Should your circumstances prevent speediness, all you need to know is that 1) her magic spells (that can never hit you if you're crouching) temporarily turn you to stone, and 2) she chucks out baby snakes that can be exterminated with the faintest whip wiggle. Odd that Nintendo of America allowed Medusa's chest to be exposed, considering some of the other tweaks made to the North American version.

Rather than heating things up, block 2-3 is a sort of reprieve. The main feature here is the river's alternating current. If it's going right, you need to make sure that you don't indulge in the speed and slam into an enemy or bed of spikes; and if it's going left you need to fight for forward movement while recognizing that the direction could change the next second. This was a feature that appeared twice in CV3, except that the shifts in current were dictated by where waterfalls landed from upper levels -- and that, as a consequence of Trevor's abilities and the selected enemies, it was a lot harder. In SCV4, you're up against lenient smatterings of creatures such as passive, flying gremlins and slow bats. In a way, the minimal level of challenge here makes the river's whims feel more ambient, as if it's a natural consequence rather than strict level design made to test players' mettle -- and, for me, it supports the theme of morose restraint, of dark quietude, that we've been noting thus far. The storm clouds in blocks 2-1 and 2-2 weren't heavy just with the literalness of water. Fantastic rock formations, especially those smooth, depressed-top tiers in the second screenshot above.

Below, I've included "behind the scenes" looks at the two background layers of block 2-3 (thanks go to Badbatman3

for ripping them). I feel it'd be a mistake to glide by this

inventiveness, hard to see even while playing the game. Are those

pillars in the lower frame botanical or geologic?

We'll be looking at stage 3, one of the game's most impressive sequences, next.

Incoming mini-post because there were several things I'd forgotten to mention in Study No. 2 that I want to touch on before I forget (okay, I wouldn't forget, but it's easier to formulate a new post knowing that I've gotten these bits out of the way, or at least approached them).

#1: Although I'd mentioned that stage 1's block 1-1 presented the skeleton enemy in its most primitive state, I did not mention that block 1-2 supplies several fully developed (let's call them aggressive) skeletons that throw bones and jump. Another comparison with previous games must be made. Aggressive skeletons in Castlevania and Castlevania 3 were the closest thing that Simon and Trevor had to doppelgangers. If you tried to outrun such a skeleton, it chased after your avatar at an equal speed; yet if you tried to confront this skeleton, it would retreat. All the while, the skeleton would be tirelessly throwing one bone at a time in your direction with very little pause after a throw so that it could continue along its advance or retreat with little downtime. Consequently, the best trick to defeating skeletons was to bring them towards you by retreating and then striking either at the moment that the skeleton's brief offensive action made it immobile, or, provided you were close enough, striking in the midst of its advance. Of course, you also had the options that the subweapons afforded, such as throwing a splash of holy water on the ground between yourself and the skeleton, retreating, and letting the skeleton take itself out by advancing over the water.

SCV4 removes that sort of inversely-mirrored behaviorism from its aggressive skeletons. Instead, they erratically walk to the left and right while facing you. Their movement is slightly slower than Simon, and, barring rarities, if they do jump to close a space between themselves and Simon, they'll only do it once. After they've landed, they're stuck to that surface. On top of this is their new bone-throwing pattern: like their patrolling movements, they don't really have a pattern. They'll throw a bone when they want to. What all of this means is that SCV4's aggressive skeletons aren't so aggressive, and their erratic behavioral elements aren't enough on their own to create sufficient tension. Stage 9 has a memorable moment with a hardier skeleton, but outside of that case, whose difficulty is bound to its unique spatial conditions, there's not a lot else. We should also remember that Simon can whip upwards in three directions. Ordinarily, if a skeleton were on a level above one's avatar, the player would need to reach that level to deal with that skeleton (a classic example is the first room of Castlevania's fifth stage), or utilize the axe subweapon if they had it. However, if a skeleton is on an upper level in SCV4, a player can whip above themselves and deal with the skeleton in a way that the skeleton can't respond to with matching competence.

#2: Simon can now adjust himself in midair following a jump. Previously, a jump in a direction meant that your avatar was unalterably going in that direction. It was a commitment, and like the left-or-right whipping it was a mechanical restriction that gave the games their peculiar challenge (unlike the restriction on whipping directions, the limit on jumping had some realistic basis -- unusual for action-platformer games of the time (and still somewhat unusual!)). Now, with all of these comparative criticisms it's important to clarify that SCV4's edits to the repertoire aren't problematic because they're disrupting "the way things should be." If the series had forever and exactly stood by the model of the NES games, there would have been stagnation (and it is arguable that some of that stagnation can be felt in parts of CV3, even during parts of apparent novelty). SCV4's mechanics are being criticized for their undermining of level design. It is also important to clarify that we're hardly to the point of a game like Symphony of the Night, a game whose bestiary is partially taken from that of a preceding game (Rondo of Blood), despite the level design having changed from an action emphasis to one of exploration, and despite the character being the opposite of the mechanical archetype of the Belmont. And it is lastly important to clarify that these criticisms -- either of SCV4 or SotN -- do not necessarily lead to wholesale damnation of the targets. It will be part of my task, in this tour of SCV4, to bring up positive points that make a case for the game's value, because I do believe that it is valuable. This will be a difficult task: SCV4's value, I think, lies beyond a hard analysis of how a given stage "works." Rather, it lies in the real-time act of playing, of absorbing its converging and accumulating atmospherics. This is a value that, in a sense, lies beyond words and beyond defense.

~

#3: This is a preemptive comment, since the material being used for it comes in part from SCV4's second stage. ActRaiser was released for the SNES on December 16, 1990. SCV4 was released on October 31 of 1991. Two screenshots from the former can be seen above two of the latter. I use ActRaiser as a comparison for its stages' similar thematic emphases and the small span of time between it and SCV4 (true, a year in the 90s meant more for videogames than it does in the 2010s (this is not to say that it took a year for SCV4 to be developed; more likely, it was half of that), but not to the extent that the comparison can be undermined). I'd like readers to look at ActRaiser's screens and notice several things: 1) the binary division between a foreground and background, 2) the simple manner in which the grounds' features are layered, 3) the minor number of discrete details, and 4) the foreground's "literal" colors ("brown things" are brown; "green" things are green). This forest's landscape can be quickly understood: a grounding dirt path, occasionally capped by short grass, its cross-sectioned side pure black; bushes and tall grass lining the side of the path furthest from us with little done to mask where the tiles end, giving their lines a domesticated appearance; the bold bodies of trees rising up from these bushes or tall grasses, each of whose crown of foliage is often individualized from others'; and lastly, the background as a single scrolling unit that, to embolden the foreground, devotes its real estate to minimal details and a limited palette of pale greens and dark blues.

And then we have SCV4. Curious, almost animalistic clumps of dirt lead the foreground; behind them are straight shots of grass that are a mixture of green, reddish-brown, and ocher. This vegetation more resembles a lane of tightly packed, ribbed virescence. The path has a central tread of spotty dirt lining it with breaks in between of grass. Behind this is what appears to be an elevation of dirt supporting yet more, and messier, grass. From here, trees with purplish trunks rise up. Their leaves aren't so different from those of ActRaiser's, but it's hard to tell them apart from the (bluer) leaves of the trees behind them, and their masses are interwoven. Also note the reddish, unexplainable diagonals embedded among the leaves. Deciduous trees' purple trunks behind the first row sport bulbous forms that make each resemble a baring of internal organs. Between them and the frontal trees are periodic orange masses that must be mounds of dirt and rock. Most distantly is a row of coniferous trees. All of this detail is confined to two layers (meanwhile, above, four layers of storm clouds roll on by). The second screenshot of SCV4 has been included just to show what the foreground, and those "animalistic clumps of dirt," become once Simon has walked far enough: a subterranean cross-section that seems more akin to the bumpy, scaly hide of some creature.

If there is another Super Nintendo game that matches the oddness, "tasteless" density, and knobby grotesqueness of what's just been shown and described of SCV4, I'm not aware of it. I have, now and then, seen its visuals written off as ugly. What I want to propose here is that that isn't an adequate dismissal. SCV4 has moments that I would call beautiful; it also has moments that I would call ugly. There is no part of me that wants to re-brand these ugly moments as "beautiful" for justification, because their ugliness, similar to a painting by Francis Bacon or Philip Guston, is their justification. To me, SCV4's look is representative of an enthusiasm for the new, powerful technology of the SNES, an enthusiasm that wasn't so concerned about checking itself or being levelheaded, and which was filtered through the artists' interpretation of what Castlevania was, or could be. There is a baroque fecundity in this ugliness, and it is found in no other Castlevania game.