An ivy-strung fence erupts from the ground upon Simon's arrival, delaying the music ("Simon Belmont's Theme" (around forty seconds longer than CV3's first stage theme, "Beginning"!)) for several seconds until it has fully risen. Stage 1 is, as one might expect, a primer for first-time players, and the game's easiest stage. What makes it remarkable is how committed it is to showing an environmental narrative that is distinct and coherent. Block 1-1 sees Simon walking through the unkempt courtyard of a villa. 1-2 is the first half of the main building's interior, the ruined structures atop the building, and the latter half of the main building's interior. 1-3 is the final block, and comprises a barn-like complex behind the villa. The heroic exclamations of "Simon Belmont's Theme" are tempered by an earthy, leather-bound ensemble, seeming to both acknowledge the subdued rusticity of the environment and the motivations of the character.

Block 1-1 gives the player several skeletons and bats to fight, but holds back by not having the skeletons throw bones or jump and by decreasing the bats' flight speed. At the moment, the game is only concerned about presenting their basic behavior. It also provides players with the second whip power-up, maximizing its length/rage. There are two pits in the ground near the block's middle and end. Rather than legitimate threats (it is clear that the pits are uncrossable, and no enemies are nearby to knock you in), they are prods by the developers to tell you to utilize the doors set in the fence to cross over to a different, walkable side. I first played SCV4 with a sufficient amount of experience with videogames to instinctively press up on the D-pad when in front of one of these doors to open them. Other people, no doubt, will lack, and would've lacked, this instinct; thus, the pits.

A new enemy, the bone pillar (or dragon skull cannon), appears in 1-2. Here is where SCV4's main problem becomes apparent. Although the bone pillar is an immobile enemy, it makes up for this by having projectile attacks: three fireballs shot out from the facing skull's mouth. There is a pause after this minor barrage for the player to get closer. Prior to SCV4, the only way to combat the fireballs was by flicking out timed whips to nullify each fireball, or by jumping with no hesitation in between them (much harder to do). When it comes to SCV4, however, two strategic options are added to the list: you can also either let you whip dangle and let the incoming fireballs hit it and fizzle out -- keep holding the attack button, and Simon's whip will shield the front of his body -- or you can duck to let the fireballs pass over Simon's head (furthermore, Simon is capable of shuffling around slowly while ducking). On top of this, SCV4's bone pillars' barrages are slower in both the fireball movement speed and the time taken for a new barrage to follow up the last. Bone pillars will continue to appear during the rest of the game, but the only change that will be made to them is their hardiness -- instead of taking three hits to defeat by a fully powered-up whip, they will require four. The issue at hand here, then, is mechanical excess; or, if one prefers, a lack of parallel development in the opposition's patterns to account for the mechanical changes that have been made.

Visually, block 1-2's interiors read as a combination of Castlevania's second (2) and third (3) stages. There are the rotund, brickwork columns (2), the primary contrast of orange and blue in the walls and interactive structures (3), the patchily worn walls (2), the wide, round-arched windows (3), and the touches of ivy (3). These comparisons may appear generic or arbitrary, but they're not so implausible when considering the series' love for referencing its past in small and large ways. It's also interesting to see that SCV4 maintains the spirit of the strange color choices of the NES games that reached a peak of bizarreness, gaudiness, and unusual beauty, in CV3; it is perhaps just not as quickly apparent, because SCV4's tones are duller, darker, and the relevant colors are distributed with greater discreteness. Bloodlines, released in 1994 on the Sega Genesis, remains the only post-SCV4 Castlevania to sustain this look in some ongoing way, such as its purple sky in the last part of its Tower of Pisa stage, or the setting for the Golem boss, with its backgrounded green columns and their magenta reflections in the water below -- yet, overall, the game's colors (taken on a room-by-room basis) are straightforward, "logical," although it is tempting to say otherwise due to their hard, snappy directness.

A pot roast, an item that restores much of Simon's healthbar, should any of it be lacking, is hidden in a wall soon after the first bone pillar, released by hitting three bricks. This secret is positioned right next to a candle that most players will be compelled to whip, making the pot roast very hard to miss. This is a nice instance of the game revealing a part of itself purely through its environment. It is impossible to make a definitive statement here about what all players will learn through the unveiling of the pot roast, but it seems reasonable to assume that many will think, "This wall had something in it, so... maybe other walls will, too" -- a correct assumption! And SCV4 is smart enough to have two other breakable masses in its first stage, so that diligent players understand that the first breakable wall is not a unique instance.

On the other side of the wall, in the candle, is an invincibility potion. Snagging one of these (held in definite candles or randomly dropped by defeated enemies) grants the player a handful of seconds wherein nothing can hurt them. I've never quite been convinced by the inclusion of this item. Sure, at its best -- and worst -- it's merely superfluous, but then why bother? It made the most sense in the first Castlevania, whose stages/blocks were small, and its action compact, enough to make a few seconds of unhindered movement enjoyable. Past that title, the games' spaces have stretched out in such a way that the claiming of a potion feels more awkward than relieving. It seems to me that a better usage of the potion, once a controller with more buttons than the NES appeared, would have been as a storeable item, and one that players could not have multiples of.

True to the first stage's intent to introduce its aspects step by step, players are given an opportunity to test out, with no chance for failure (see the first screenshot above), another new function of the whip: using it to latch onto somehow-levitating metal rings and swing past an otherwise fatal or unreachable space. Most would probably critique this feature for not exploring itself enough, and I would agree. It only starts to become something more than its basic idea in the last couple of stages -- most of all in the clock tower -- yet I still believe that it should be appreciated for the small variety it brings, and also for how naturally it controls. The malleability of Simon's swinging movements really is a miracle of programming. Note that the bluish-brick-supports are given a structural context by the columns; also note that the nocturnal vista, rather than being a totally new thing, is a further revealing of the sights seen through the windows in the building's interior.

We enter the barn-like portion of stage 1. Enormous mounds of hay rise against the night sky, and wood becomes a dominant building material. A sample of the game's visual deviousness can be seen in the night-shaded wood of the fence's planks and the interior's wall being a mixture of a brownish purple and deep blue, rather than a couple or trio of lighter and darker browns that we would expect. It can also be seen in the specks of purple stars. Two unique enemies inhabit block 1-3: the viper swarm, seen in the screenshot above, and Mr. Hed (SCV4 has a love for wordplay), seen in the screenshot below. Viper swarms attach themselves to ceilings and drop to the ground when you're below them. Those new to the game might get hit by the first viper swarm, thinking it an odd scenic detail (or altogether missing it) while fiddling with the line of candles. Otherwise, it is hard to imagine these creatures posing a continual threat. Once they do land on the ground, their rate of movement is the slowest of anything in the game, and they have no offensive options. Had their placement been combined with an enemy that complicated things, the viper swarms could have produced a legitimate action dynamic. As it is, they are simply "things to whip."

Mr. Heds appear nowhere else in the game aside from block 1-3's introductory room. They are essentially slightly faster ghosts (ghosts, appearing first in Castlevania's second stage, are small spirits that materialize in midair and slowly home in on your avatar) that come your way once you're within a certain proximity. Because they do only appear in this one room, not a lot can be said about how they contribute to the game, outside of reflecting the barn/farmyard theme of block 1-3. Again, the first one could hit novices, since it does somewhat blend into the ground and advances quickly.

Part of CV3's first stage is echoed in SCV4's similar inclusion (see above) of a walkway studded by platforms that flip if they are jumped upon, and aerially patrolled by the sine waves of medusa heads. Unlike CV3, SCV4 offers no non-fatal crash course in the flipping platforms' behavior, nor are the platforms color-coded/textured in a significantly different way from the walkway's solid parts to indicate their specialness. This seems strange, given the exemplars thus far. Even so, it doesn't strike me as too damning, considering what this new Belmont can do. Thin -- or actually skeletal (not outside of the realm of possibility, given the game, and upcoming boss) -- horses are seen grazing outdoors.

And what can this new Belmont do? Well, much of it's already been put on the table. Eight-directional-whipping, though, has not. Until SCV4, whipping was a left-or-right affair. Threats that exceeded the default plane of offense either had to be avoided, dealt with by jumping and whipping, or combated by a subweapon like the axe. Yet, like in the case of the bone pillars, Simon's capabilities have grown without enough equal counterpoints to justify such growth. I've chosen the screenshot above because it demonstrates (I admit, to a uniquely high degree) the occasional ridiculousness of the aforementioned imbalance's results. If Simon could only whip to the left or right, he would at least have to descend the staircase and reorient himself so that he could attack from the steps. Now, not even that is required: a player can jump up, whip downwards, and strike the viper swarm, turning what was already pretty much a non-challenge into a non-event.

Heavy shadows surround the platforms' and staircases' edges. It's not as obvious as platforms being supported by columns, but it's a way of giving these structures a physical presence outside of their interactivity. I read the shadows as saying that the platforms and staircases extend from the wall.

Rowdain, stage 1's boss, enters from the right side of the screen atop a skeletal mount. The two move back and forth, but never advance enough to the left to hit a player resting on the lone platform. The mount fires a small, lazy fireball from its mouth every three seconds. Its weak spot is its head. Take care of the horse, and Rowdain, now grounded, walks about like a rickety fencer, stabbing his lance out if you get too close. Strategy-wise, there's not a ton to say here: if you can dodge the easily dodged fireballs, you've mastered the toughest thing about this boss. When he has one bit left on his healthbar, Rowdain explodes, reassembles, and leaps into the air, trying to nail you with a downward thrust. This could hit some people, just because it's a bit of a surprise, but once a player has gathered their wits they're only a single flick away from winning. Everything should be over in less than ten seconds with a metal whip and cross/boomerang subweapon.

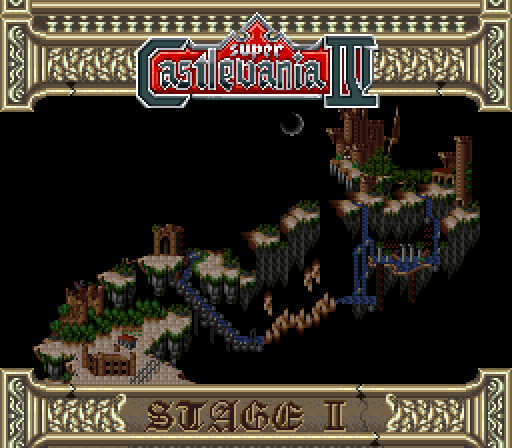

Stage 1 is complete, and the game moves on to a map that very generally shows the upcoming route and its setting(s). I've always loved this map, and I recently came to realize that it's not just because it gives the adventure that extra grounding of macro-sequentality; it's also because it so resembles early European landscape paintings, such as the ones by Joachim Patinir -- the roundish foliage of trees, the curious massing of the land, how so many things are visible at once, the styling of the architecture, and perhaps even the colors' tones -- and that this resemblance fits so well into the "antiquarian" world SCV4 is representing.